|

Is there a fast track to becoming an Architect? |

||||||||

The last few articles in this series have documented what I consider the standard approach to becoming an architect to be, the TOGAF role structure and the key concerns around performing the role of an architect day to day.

I've built the foundation of understanding the role, specifically to ensure a level of understanding of the attributes and activities of an architect. This is key, as in this article I'm specifically looking at the idea of whether or not it is possible to fast track the journey to become an architect. Posing the question, could you take an individual with the capability to perform the role and move them in quick succession through a series of tasks to establish possession of the skills required to operate as an autonomous architect in their own right.

Let me start by saying that there are several assumptions associated with this scenario. The individual, the 'candidate architect' would have to be aware that they are on a journey to display their skills as an architect. The capacity or capability to perform the role would have already been pre-judged as being present, and the candidate would have a knowledgeable support network around them.

What should they be tested against?

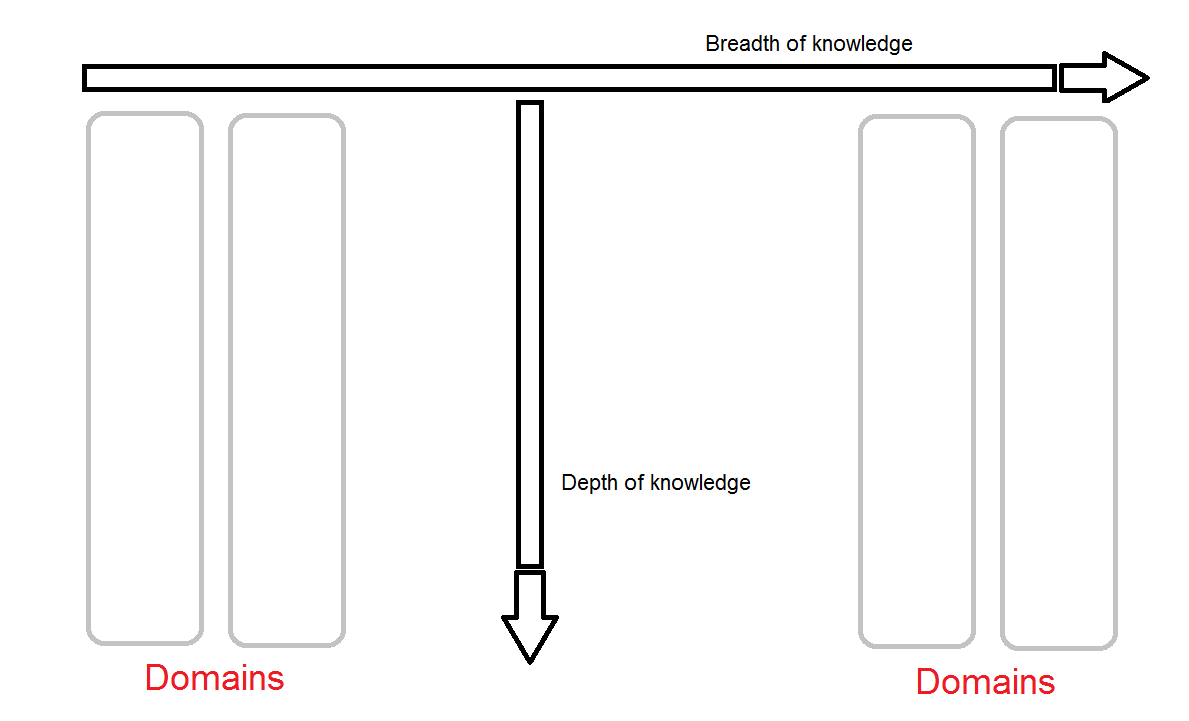

As stated above, I've already put together my view on the activities an architect performs. There is a key factor here in differentiating between architects and subject matter experts (SME's). This is import in that these two categories of role are very different, but can often become confused with each other. To understand exactly 'what' we should test candidates against we need to understand the difference between these two type of role.Subject matter experts

Subject matter experts are people with deep knowledge in a business area or capability. They have deep understanding of their area of functionality, but its a very narrow view. Typically their skillset is specific to a field of business services or technology, such as payments, networks or services. They do not have a breadth of insight across multiple fields or processes. This makes them ideal team members if you want detailed information, at a very granular level, but if you want someone who can be reapplied over many content areas, SME's will struggle as they will be outside of their comfort zone.

Architects

In comparison to the SME description above, Architects have a much wider breadth of knowledge across many fields of technology and business capabilities. They may have more detailed knowledge in one or two fields, specifically where they came from, but as a rule they have limited visibility over other process and technologies. This means that as a member of a team, they are deployable across the whole spectrum of a solution as their skills are not specifically tied to one area of knowledge.

Flexibility and not detailed knowledge

From the descriptions above we can determine that the skills an Architect should have are not based in a specific technology or business process. They should sit above this, as they should understand how to examine and interpret technology solutions and business processes, but they should not have detailed knowledge of them, as that's why you retain your SME's.When you consider this, it effectively dictates what you would ask a candidate architect to prove. You would NOT ask them to understand each of your business areas, or processes, but instead ask them to show the skills to discover those areas, integrate with the SME's and extract the right information that is pertinent to the solution.

What's missing from this process?

The above describes the technology and business process discovery but it intrinsically hints at needing stakeholder skills and interpersonal skills to be able to operate successfully. They are a little harder to measure as they are less tangibly proven.The second big factor missing here is the experience and ability to handle the pressures of going through this process. Knowing a task is one thing, but presenting that task back, thinking around it, defending your position when appropriate, or moving on it when its not, are all skills gained from actually going through the architectural process. Experience of previous roles gives people a depth of character that gives them confidence within a business operating model. At its simplest description, discovering and documenting options is a key skill that can be learned. Presenting that options paper back to senior stakeholders with confidence, explaining the process, facing down challenges and holding your nerve is an entirely different skill that is not learned, but more like 'forged' through going through the process repeatedly.

So in summary, I'd say that yes, there is a fast track to 'learning the skills required to operate as an architect'. But I'm separating out that just having the skills does not mean that the candidate can operate as an architect, they need that forging experience to have the confidence and prescience in a room to carry through their architecture directives.

|

What do you need to know to become an Architect? |

||||||||

MetaModel for a professional role

Any professional role comes with a common set of terminology, activity description (processes) and method that allows for a common language within its industry. Architecture is no different from this, for example, if you are a practicing Architect within company '1' and you move to company '2' there should be a consistent set of architectural language across both companies, within some variances, based on company practices.Similarly because the activities, the 'what', of being an Architect are based on the structures they follow, such as Governance, Design and Assurance they tend to be common in nature, whatever the industry or the subject. Conceding that the detail in the activity is different, such as whether the design or business subject is Telco, Financial or Marketing, but detailed knowledge of that subject makes someone a subject matter expert, not an Architect.

Lastly we have the Method, or the instruction set, the 'how' to perform architectural processes. This is the bread and butter of being an Architect, this is the way you think about framing an argument across a variety of stakeholders, or the way you research and collate a set of options on a decision paper.

Applying the above model to being an Architect

So applying the above model to the role of an Architect we can list out several key items that would populate this MetaModel. Note that this isn't exhaustive, but rather an initial set of data, the common things you should really know. This should be treated as a starting guide, a set of terms or topics to make sure that you are at least aware of and ideally able to describe in good detail. I stress this as I've held quite a few interviews for Architects and been surprised how many candidates are not familiar enough with some of these terms to be able to describe them in sufficient detail.

On top of this I've added a section on who would engage in the topics raised here, after all there are several types of Architect, and knowing what they are and what they do is vital to being a functioning architect. Note that these roles are largely taken from the TOGAF model.

Roles

- 1. Enterprise Architects

- 2. Solution Architects

- 3. Service Architects

- 4. Application Architects

- 5. Data Architects

Terminology

- 1. Architecture Review Board

- 2. Governance

- 3. Assurance

- 4. Solution Design

- 5. Architectural views, such as Conceptual, Logical and Physical

- 6. Building Blocks

- 7. SOA - Service Oriented Design

Activities

- 1. Stakeholder Management

- 2. Review and approvals cycles

- 3. Decision papers & impact assessment, including things like Change control

- 4. Stakeholder specific formatting of designs, tailored to their specific viewpoints

- 5. Architectural levelling, such as 10,000ft view, 50,000 view etc. Used commonly to describe the level of detail a solution is at.

Processes

- 1. Modelling processes, i.e. How do model solutions

- 2. Discovery processes, such as how a process, system or application works

- 3. Documentation processes, such as common MS office based work

- 4. Options papers, where several options are presented, they are compared and a recommendation is put forward to form a complete argument

- 5. Alignment to Principles and Patterns - Showing Architectural thinking and alignment to Strategy

I would consider all of the bullet points above as key things to be aware of i

|

The standard approach to becoming an Architect |

||||||||

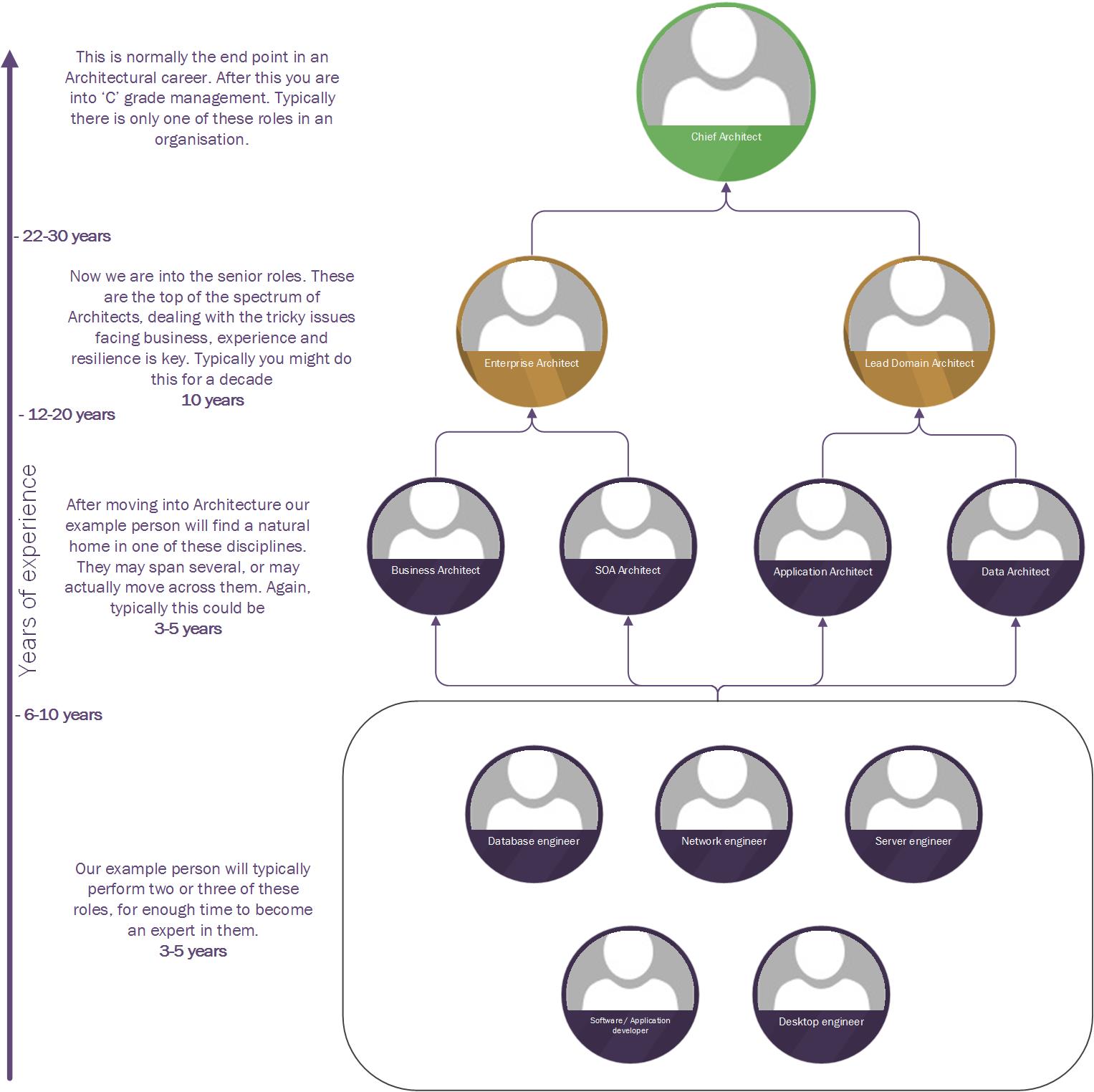

Is there a standard approach to becoming an Architect? I'd consider that there is a standard pattern to becoming an Architect, but the individual steps on each individuals journey is likely to vary quite a bit based on drive, opportunity and situations that arise allowing an individual to move forward.

A foundation element in this approach, whatever the specific path, is that the individual works through the existing discipline, rises to the top in recognition and moves up or sideways to gain more experience or responsibility. In this way the individual is building both breadth and depth of experience in a variety of fields. A repercussion of this is that eventually the individual ends out with a broad range of experience across several disciplines. This makes them an ideal candidate to step into Architecture, whether that was their intended goal or not. You can test this out, do a straw poll in your office, how many people intentionally 'become an Architect' instead of 'naturally fell into it after a career in many other disciplines'?

We can model this as:

Breaking down the above image we can see that a common career trajectory into Architecture is via several disciplines. Once a person hits a certain level of maturity in the discipline they currently in, they expand their skillset by moving around, or up. As the person gains skills and moves upward each movement becomes harder and harder as the roles gain in seniority, and availability. From bottom to top is a shrinking model of available roles, with each position above typically having a significantly smaller number of positions available at each level. This arrives at an end point with the chief Architect role, which is typically a single role within an organisation.

As above in my intro, this model encourages individuals to gather both breadth and depth of skill in each field. This depth of background experience is one of the key components that allow an Architect to successfully complete normal architectural tasks, such as decision papers and end to end solution assurance.

One element of this that is especially true is an Architects ability to understand all the different aspects of a solution, and being able to play that solution back in a format suitable for a variety of stakeholders, at their level of view. This interpretation of a solution, played into the Business stakeholders is a key skill for Architects as it allows them to convey often complex, difficult solutions to key business representative in a consumable format for them. This Assurance role gives clarity to the business on the fact that defined solutions are aligning to their strategy, and that the project spend is delivering what they want, and what they think it is delivering.

Think of it as, Assurance requires credibility, and credibility only comes from established, evidenced experience.

|

The journey to becoming an Architect |

||||||||

A common issue that I see in many organisations is one of resourcing and quality of resource. There would appear to be significantly more demand in the UK market for Architects of good quality, than there are actual Architects out in the 'resource pool'.

Now there's likely a few factors involved in this;

- 1. Sometimes the criteria for actually identifying what an Architect IS can be a bit vague, and is open to considerable amounts of interpretation, this is across both organisations and Architecture industry bodies.

- 2. The path to becoming an Architect is typically quite a long one, with an individual having to traverse many different disciplines, gaining experience in each, and practicing a set of 'over the top' skills as well, such as stakeholder management, to be able to operate in quite a demanding space within an organisation. This is generally not a fast process, taking time and effort, becoming familiar with a lot of different challenges, being tested in them, and becoming a pretty resilient character.

So if you've got aspirations to get into Architecture, how do you go about it? What's considered the 'traditional' path? Is there a fast track? All things that I'll cover in a series of blog posts. Its going to be a pretty big picture conversation, so

I'll link each one off from here, taking an Architectural approach if you will, building up each part of the story so that you can see how it comes together. Note as well that this isn't a guide to TOGAF. There are much better places to learn that than here, I'm simply applying some of the core elements of the framework to show how it can help you think about being an Architect. TOGAF may appear somewhat 'High brow framework' sometimes, but it has been developed over the years with a common sense approach to how to actually perform Architecture tasks, as such it can give us some really good insight into how to think like an Architect.

My initial list of topics is below, but as is the case with any Architect, I'm likely to change it as I go along.

- 1. The standard approach to becoming an Architect

- 2. Is there a fast track approach to becoming an Architect?

- 3. What do you need to know, to become an Architect?

- a. Architecture roles

- b. Architecture domains

- c. Facing into a Business as an Architect

- d. Common 'approaches' (get out of jail free cards) that Architects use

- 4. What should you be able to knock out the park, day after day as an Architect?

- a. Options papers

- b. Transitional state views (AS-IS in comparison to the TO-BE) typically showing Tactical decisions and whether they align to an overall Strategy

- c. Governance submissions and responses

- d. Conceptual, Logical & Physical architectural views

- e. Principles and Patterns

Think I'm well off the mark in any of these articles? Feel free to provide a counter balanced view, after all, that's a key aspect